In the Twitter profile for this blog, I note that it is an exploration of Mary Magdalene in history, spirituality, culture, and the arts. Mary Magdalene is so embedded in the cultural history of the West that she often pops up in unexpected places, to my delight, and I’d like to dedicate this post to one such instance: one card in the classic 1909 Rider-Waite-Smith tarot deck.

Mary Magdalene and the tarot

Even before The Da Vinci Code there were multiple threads of mystical interest in Mary Magdalene. One perspective with a lot of momentum was sparked by Margaret Starbird, in her book The Woman With The Alabaster Jar, which will enjoy its 30th anniversary later this week (June 1, 2023). In it, Starbird sought to advance the thesis of Holy Blood, Holy Grail, that Mary Magdalene was literally the wife of Jesus. There is quite a lot to write about Margaret Starbird’s work, but relevant here is the fact that she interpreted the origin of tarot cards as a kind of hidden catechism to keep alive secret knowledge of Mary Magdalene’s status. She even published a book on the topic in 2000, called The Tarot Trumps and the Holy Grail. I personally was not convinced, and had believed that it would be the only place where Mary Magdalene would intersect with the topic of tarot.

In August of 2021, however, while casually exploring the art of various tarot decks, both antique and modern, I noticed something interesting and couldn’t find any evidence that anyone else had seen what I was seeing. It’s possible that someone before me noticed this and it’s buried in some commentary on the tarot, but even now I’m unable to find any information about it, and to be honest, doing a deep dive into the history of tarot art isn’t where I’d like to spend my time. So I’ll submit it here for your consideration, and would love to hear if anyone has any ideas or suggestions or elaborations.

The Rider-Waite-Smith tarot deck

In 1909, Arthur Edward Waite, an occultist and Holy Grail legend enthusiast, commissioned an artist named Pamela Colman Smith to create illustrations for a deck of 78 tarot cards. It was innovative at the time because illustrations would be shown on all of the “pip” cards as well as the tarot trumps. The art itself contained motifs and symbolism mostly related to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an occult fraternity in England of which both Waite and Smith were members, but it also included some references to Holy Grail legend and common Christian iconography. It’s unknown how much of the symbolism was specified by Waite to guide Smith’s designs and how much was contributed by Smith herself, so it is consequently very difficult to say where specific ideas originated. This is unfortunate because I would dearly love to know how an image of Mary Magdalene snuck into the mix.

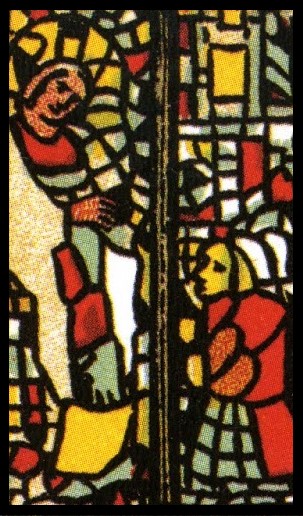

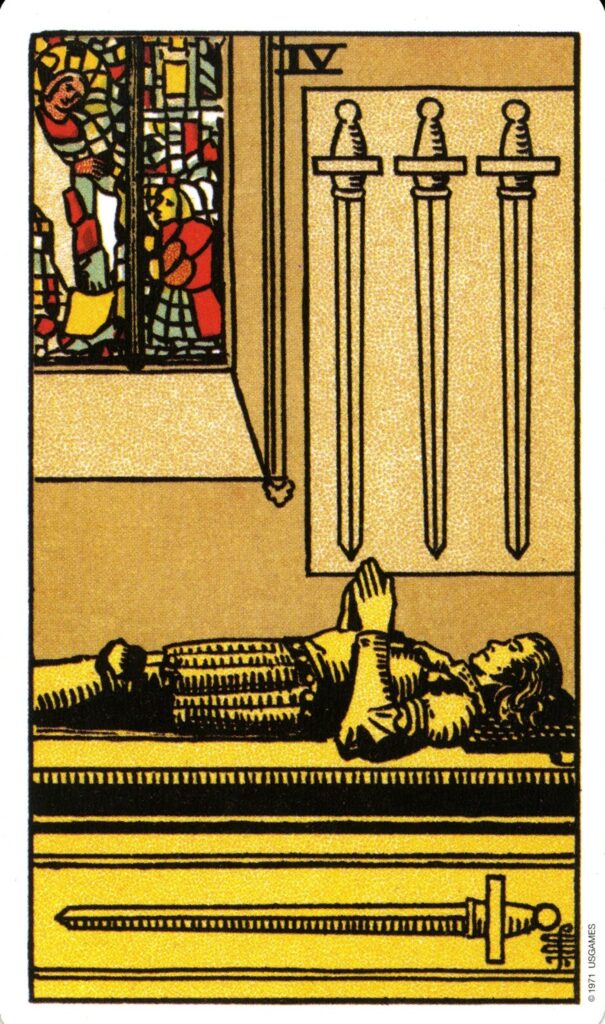

On the Four of Swords card, the main imagery shows a knight in effigy on a tomb inside of a cathedral. Hanging over the knight to the right are three swords, with a fourth lying horizontally beneath him. Above him and to the left there is a stained glass window which has been described in a variety of ways: it’s Jesus blessing or healing a supplicant / penitent / follower, or maybe it’s a woman and a child, or maybe it’s someone praying to the Virgin Mary, and so on. After sifting through various books and forums on tarot I’ve not seen any consensus about the stained glass imagery. To my eyes, however, it is a fairly standard noli me tangere motif–the scene from the Gospel of John in which Mary Magdalene encounters the risen Jesus in the garden.

Noli Me Tangere

Noli me tangere is Latin for “touch me not.”

Jesus saith unto her, Touch me not; for I am not yet ascended to my Father: but go to my brethren, and say unto them, I ascend unto my Father, and your Father; and to my God, and your God.

John 20:17 (KJV)

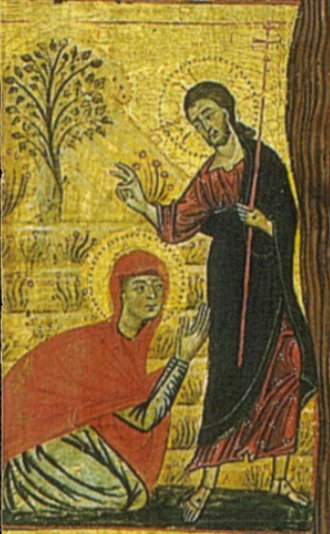

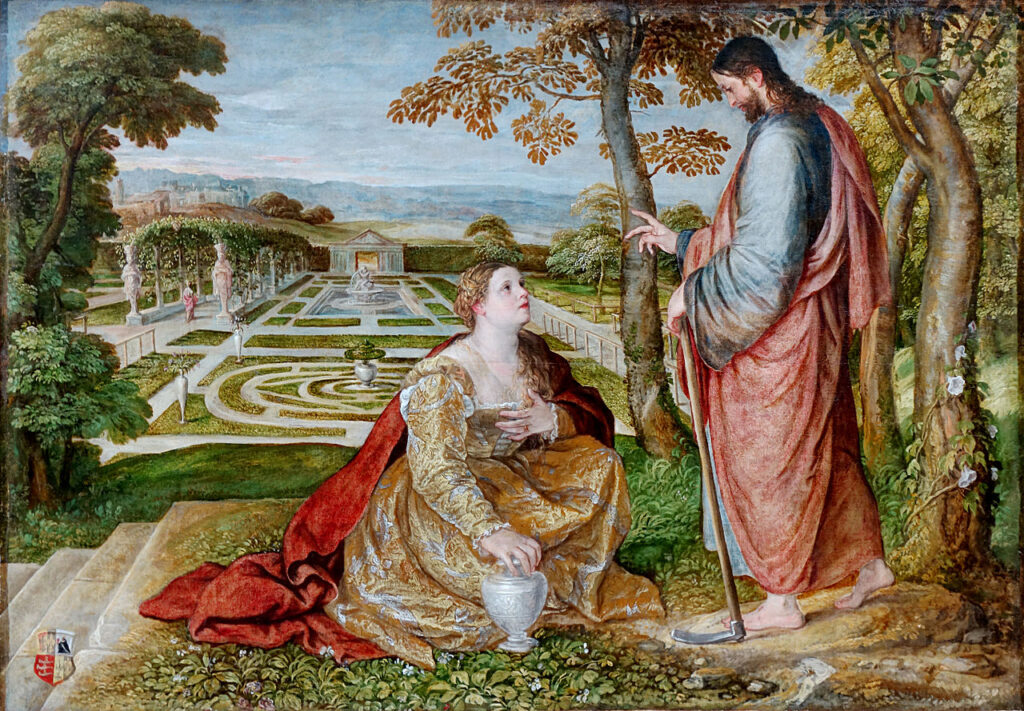

This is an extremely common theme in Christian art from the late Middle Ages through the Renaissance, represented in sculpture, paintings, and mosaics, in murals, manuscripts, miniatures, crypts and cathedrals. Often in these paintings Jesus is dressed as a gardener, occasionally carrying garden implements, and sometimes he carries a flag representing his triumph over death. In some images he is facing away from Mary, and in others he faces her. Sometimes he holds his hand palm outward toward her in what we would recognize as a “stop” gesture, and sometimes he makes a gesture of blessing. Mary Magdalene is typically portrayed kneeling before him, or if she is standing she is usually leaning forward as if to touch him. Often the empty tomb is depicted somewhere in the scene, and sometimes Mary Magdalene’s jar is present as well.

Detail from Maddalena penitente e otto storie della sua vita (Penitent Magdalene with Eight Scenes from Her Life), by Master of the Magdalen, 13th century, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence.

No. 37 Scenes from the Life of Christ: 21. Resurrection (Noli me tangere), by Giotto de Bandone, early 14th century, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua.

Noli Me Tangere, fresco by Fra Angelico, 15th century, in the Convent of San Marco, Florence.

Noli Me Tangere, by Franciabigio, 16th century, Museo del Cenacolo di San Salvi, Florence.

Noli Me Tangere or Christ Appearing as a Gardener to Mary Magdalene, by Lambert Sustris, 16th century, Palais des beaux-arts de Lille.

Noli Me Tangere, by Bartholomaeus Spranger, 16th century, Museul National de Arta al Romaniei, Bucharest.

The noli me tangere motif deserves a post of its own because it’s an important theme in Christian art and is one of the most common depictions of Mary Magdalene. The important thing to keep in mind now is just how ubiquitous this imagery is. It isn’t unreasonable to think that Waite and Smith incorporated it into the design for the Four of Swords, even if their reason for doing so eludes us.

Four of Swords

There are multiple versions of the Rider-Waite-Smith deck available today. The featured image on this post is from the version of the deck mass-produced for decades, but the original “roses & lilies” deck (named for the pattern on the back of the cards) features more subtle lines and colors that make it easier to identify different parts of the composition. Here is the oldest version of the artwork I was able to locate, alongside a black & white rendering with the noli me tangere elements highlighted:

Left: Four of Swords from the 1909 “roses & lilies” deck by Pamela Colman Smith.

Right: Highlighted elements of the noli me tangere

In the image above we can see the risen Christ in gold, with a halo around his head bearing the word PAX (Latin: “peace”). He holds his hand in a gesture of blessing toward Mary Magdalene in red, who kneels before him. (It is possible that she is holding her jar, but it’s very difficult to make out the shapes in such heavy outline.) In the background highlighted in light blue is the empty tomb. To create the appearance of stained glass, all sections of the image are divided into rough shapes and colors; some give the impression of additional letters, but I was unable to detect any words other than PAX.

It’s tempting to try to guess what motivation could have prompted the inclusion of a noli me tangere scene in the Four of Swords. When the deck was published there was a booklet describing what each card was intended to represent, which Waite revised and published a year later. Its description of the Four of Swords contains very few clues:

The effigy of a knight in the attitude of prayer, at full length upon his tomb. Divinatory Meanings: Vigilance, retreat, solitude, hermit’s repose, exile, tomb and coffin. It is these last that have suggested the design. Reversed: Wise administration, circumspection, economy, avarice, precaution, testament.

The Pictorial Key to the Tarot, by A.E. Waite (1910)

One could suppose that on a card intended to represent the ideas of “retreat” and “solitude” alongside “tomb and coffin,” a generalized theme of death and resurrection wouldn’t be out of place, but that is pure speculation. Another clue, simply because it isn’t a common inclusion in the noli me tangere scenes, might be in the halo surrounding Jesus’s head containing the word PAX.

I leave it to those interested in tarot history to make of this what they will; it was my intention here only to point out that this stained glass window is a very common depiction of the risen Christ in the garden with Mary Magdalene, and to share one more surprising place where we can find her.

Do you have any additional insight into this stained glass window? Or historical information about Pamela Colman Smith’s inclusion of this motif in the card? I would love to hear about it in the comments!