It might seem strange to begin a post about one scholar with a litany of names of others, but I feel it’s important to acknowledge the people who have done the hard work of carving out an area of study around Mary Magdalene. I count myself lucky to have even met some of them personally, when we got together in New York for the filming of Secrets of Mary Magdalene: Elaine Pagels, Susan Haskins, Deirdre Good, and Diane Apostolos-Cappadona among them.

One person I’ve not met is Karen King, but I would love to someday make her acquaintance; she has done more to promote the exploration of the Gospel of Mary, in my opinion, than anyone else. My favorite translation of the Gospel of Mary, however, is still the one done by Marvin Meyer, because he imbued it with a subtle beauty that brought it to life for me.

Sadly, Marvin Meyer is no longer with us, nor is Jane Schaberg, who made me, a non-scholar, feel welcome in the same room as the academic dream team assembled for the documentary. She was also kind enough to write the foreword for my book. My qualifications for writing it, or for being in a film with her and the others, were really nothing more than a case of being in the right place at the right time, but she was gracious where some others were not. The list of stellar Mary Magdalene scholars who are no longer with us would be incomplete without also mentioning Esther de Boer, whom I was never able to meet in person, but who, like Marvin Meyer, was also friendly in correspondence.

There are others whose work I have admired for some time but have never spoken to, such as Mary Ann Beavis, who occasionally surprises me by citing my book on minor points. Others (in no particular order) are Antti Marjanen, Ann Graham Brock, Mark Goodacre, Bart Ehrman, and Stephen Shoemaker, who has effectively expanded Mary Magdalene scholarship by arguing against some ideas advanced by the others. His counterpoints lead to more robust conversations, and they have contributed to the way I think about some questions surrounding Mary Magdalene’s identity.

A note about some I’ve missed: I am still making my way through a lot of books and papers and articles and I’m sure I’ve missed some names. An example is Ally Kateusz, whose work I am aware of but haven’t yet gotten to. I’m looking forward to being able to share what I learn!

The people above and others I’ve missed have been advancing scholarship around Mary Magdalene for thirty years or more. They’ve made strides in not only expanding what we know about her but also influencing how she is perceived outside of academia. Mark Goodacre summed up this point well in his opening for an essay called “The Magdalene Effect: Reading and Misreading the Composite Mary in Early Christian Works,” which appeared in Rediscovering the Marys: Maria, Mariamne, Miriam, a volume edited by Mary Ann Beavis and Ally Kateusz.

It is rare for biblical scholars to make an impact on popular culture, but there is one area where they have achieved something remarkable. After centuries of confusion over the character and reputation of Mary Magdalene, scholars of early Christianity have achieved a coup. They have successfully persuaded novelists, documentary makers, and even film producers that Mary Magdalene was not a sex worker and, moreover, that she was one of the most important figures in the emerging Christian movement, the first witness of the resurrection, the apostle to the apostles.

That is a huge accomplishment, and yet there is still so much work to be done. It’s exciting to see now how a new generation of academics is beginning to contribute to this area of study. This brings me to Elizabeth Schrader Polczer, Assistant Professor of New Testament at Villanova University, who is taking on some of the toughest questions about Mary Magdalene and making significant headway. I met her in person once several years ago after we connected on Academia.edu, and was surprised to learn that a copy of my book checked out from the library had helped set her on her current academic trajectory. Never in a million years did I expect my book to have any influence whatsoever on Mary Magdalene studies, but if it nudged her in the direction she is currently heading then I’m satisfied that I’ve made some small, indirect contribution. I’m grateful to her for that.

What I am even more grateful to her for is that she is publishing amazing scholarship, and striking right at the heart of the matter: who was Mary Magdalene? And just as important, who wasn’t she?

It isn’t often that I read an academic paper, or listen to a podcast, and want to pump my fist and shout YES!, but this is often the case when I’m catching up on her papers and interviews. Recently I listened to an episode of the podcast The Bible for Normal People that she did with Pete Enns and Jared Byas, called “Resurrecting Mary the Tower.” In 45 minutes she laid out the high points of her work, and I recommend it to anyone who might be curious. If you’d like something a bit shorter and with a less academic approach then I recommend “Mary Magdalene”, the 30 minute first episode of a podcast called And Also Some Women.

In both podcasts, Schrader Polczer discusses her core findings and what they could mean. I’ll try to do them justice by summarizing here, but I encourage you to listen for yourself; they’re engaging conversations and it’s much better to hear about all of this from the source. It’s also fascinating to hear the story of how she went about the work that led to her publications.

Mary, not of Magdala

In 2021 Schrader Polczer co-authored a paper with Joan E. Taylor in the Journal of Bible Literature called “The Meaning of ‘Magdalene’: A Review of Literary Evidence”, in which a blazing hot argument is made against Mary Magdalene’s epithet ἡ Μαγδαληνή (“the Magdalene”) as a place of origin. Not only is there no mention of Magdala in the Gospels (or any other New Testament texts), there is no evidence that the place now called Magdala was called Magdala in the 1st century. It wasn’t until the sixth century that references started to appear. There were several places with Migdal (tower) in the name, but none of them compelling as a place of origin for Mary Magdalene. (For a detailed examination of place names relative to Mary Magdalene’s epithet, see Joan E. Taylor’s fantastic 2014 paper, “Missing Magdala and the Name of Mary ‘Magdalene.’”) What we have is a lot of guesswork and inference made since very early on that amounts to a weird and rather circular “there must be a Magdala because Mary Magdalene’s name points to it.” But does it?

The author of the Gospel of Luke and Acts, the paper points out, was fond of using a very specific grammatical convention to indicate nicknames.

- “Simon called Zelotes” (Luke 6:15; Acts 1:12)

- “she who is called barren” (Luke 1:36)

- “Simon called Zelotes” (Luke 6:15; Acts 1:12)

- “a sister called Mary” (Luke 10:39)

- “a man called by the name Zacchaeus” (Luke 19:2)

- “Judas called Iscariotes” (Luke 22:3; 6:16)

- “Joseph called Barsabbas” (Acts 1:23)

- “a young man called Saul” (Acts 7:58)

None of the locations where the author uses this language indicates a place where someone hails from, so why would that be the case for Mary Magdalene in Luke 8:2, where she is referred to using the same “(someone) called (something)” convention? Place names are indicated quite differently in these texts, leaving us to believe that this author, at the very least, considered “the Magdalene” to be a nickname.

If not her hometown, then what does “the Magdalene” mean? The paper proposes that like Peter’s nickname “Cephas” (“the rock”), “the Magdalene” can be translated simply as “the tower” or “the tower-ess.” Mary was called Magdalene because she was being compared to a tower, just like Peter was compared to a rock. This isn’t even a new idea; in the 5th century St. Jerome said the same thing.

For Jerome, an expert on Hebrew and Aramaic and entrusted by Pope Damasus with the task of translating Scripture for the Latin Vulgate, ἡ Μαγδαληνή was honorific, not related to provenance. For Jerome, ἡ Μαγδαληνή meant “of the tower,” from the Hebrew word מגדל (“tower”). It is a name that was particularly given to Mary. This interpretation is similar to Origen’s in that Mary’s moniker is seen in light of something special about her.

Elizabeth Schrader, Joan E. Taylor; The Meaning of “Magdalene”: A Review of Literary Evidence. Journal of Biblical Literature 1 December 2021; 140 (4): 751–773. doi: https://doi.org/10.15699/jbl.1404.2021.6

Various other authors have made a similar arguments over the years, but this paper makes the strongest and most detailed argument I’ve seen yet. Hopefully it will have a lasting impact and we’ll begin to see fewer references to “Mary of Magdala.”

Magdala vs Bethany

When discussing Mary Magdalene, it always seems necessary to indicate where one stands on the topic of the conflation of Mary Magdalene with Mary of Bethany. This convergence of identities is evident in the earliest Christian writings, well before Pope Gregory the Great’s (in)famous 6th century Homily 33, in which he combines the identities of Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany, and the anonymous sinner from the city that anointed Jesus in Luke. (That is a whole other story.)

Until recently, I’d never felt there was compelling evidence to defend the view that Mary Magdalene was also Mary of Bethany; after all, scholars have been assiduously untangling the identities of the various Marys for decades, if not longer. But if Mary Magdalene wasn’t from Magdala, then it’s worth considering again that Mary the sister of Lazarus is also Mary “the Tower.” These two women, as it has been pointed out before, are never in the same room at the same time. So… what if Mary Magdalene was Mary of Bethany?

First, let’s talk about Martha.

Martha in John 11

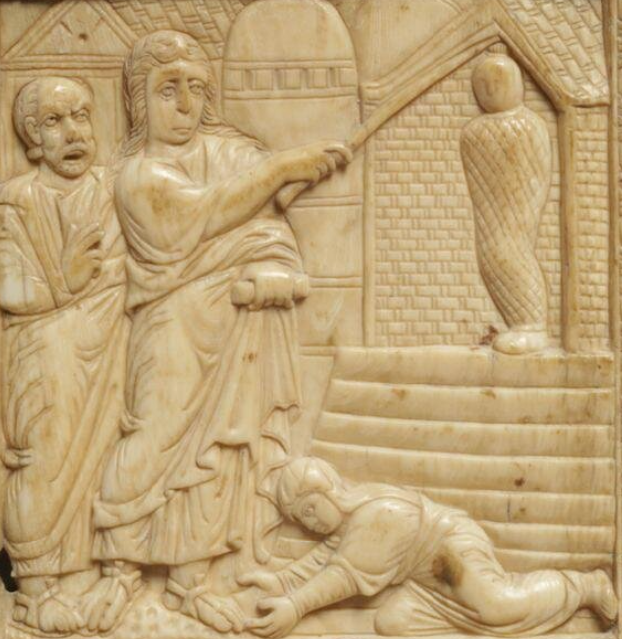

Detail from The Andrews Diptych showing the raising of Lazarus, 9th century. Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington, London. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O94187/the-andrews-diptych-diptych-unknown/

In a paper called “Was Martha of Bethany Added to the Fourth Gospel in the Second Century?” , published in the Harvard Theological Review in 2017, Schrader Polczer describes an “instability” in the textual transmission of John 11, around Martha’s presence in the story of the raising of Lazarus. What this means is that after surveying a dizzying number of early manuscripts of the Gospel of John, a large proportion of them have some kind of irregularity indicating that Martha might not have been present in the original text. This includes the very earliest near-complete manuscript of the Gospel of John currently in existence, a papyrus codex referred to as P66, from the late 2nd or early 3rd century. It’s the oldest surviving copy of the story of Lazarus.

It’s an excellent piece of scholarship, and in the Bible for Normal People podcast she shares a hypothetical reading of the scene if Martha hadn’t been present, a reconstruction based on readings in actual manuscripts that we actually have. It’s astonishingly coherent; Martha need not be present in order for the story to hang together. It’s a simpler and in some ways more sensible reading. As one of the hosts of the podcast asked though, what motivation could there be for Martha to have been added in the first place?

In other words, why should we care?

Mary Magdalene as equal to Peter

In the story of the raising of Lazarus, something called the “Christological confession” is given by Martha:

“Yes, Lord,” she replied, “I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, who is to come into the world.”

John 11:27

This confession holds weight, and importance; in the Gospel of John, Martha is the first to acknowledge Jesus as the Messiah. These words are echoed the final verse in John 20, in which the entire purpose of the gospel is clearly stated:

But these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name.

John 20:31

There is a Christological confession in all three of the Synoptic Gospels as well–all were declared by Peter, and in Matthew it confers on him the authority to build Christ’s church.

When Jesus came to the region of Caesarea Philippi, he asked his disciples, “Who do people say the Son of Man is?”

They replied, “Some say John the Baptist; others say Elijah; and still others, Jeremiah or one of the prophets.”

“But what about you?” he asked. “Who do you say I am?”

Simon Peter answered, “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.”

Jesus replied, “Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah, for this was not revealed to you by flesh and blood, but by my Father in heaven.

And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it.

I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.”

Matthew 16:13 – 19

Back to our “what if” question above. So what if Martha wasn’t originally in the text of the Fourth Gospel? Well, if Martha wasn’t present, that would mean that Mary was Lazarus’s only sister, and that the Christological confession could have been made by Mary. If that’s the case, then we should also ask: So what if it was Mary of Bethany who gave the Christological confession? After all, in the 3rd century Tertullian believed it was she who confessed Jesus as Messiah, not Martha. The crux of this question rests on whether we would like to consider “the Magdalene” as an epithet and not a place name, which would make the conflation of Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene logical. If we’re willing to hold that Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene are the same person, the question finally becomes: What if it was Mary Magdalene who gave the Christological confession?

It is very clear that in the earliest centuries of Christianity there was some kind of rivalry between those who held Peter as the one with authority to build Christ’s church, and those who held Mary Magdalene in much the same esteem, as someone who truly understood Jesus’s message. Much has been written about this already; it isn’t an isolated event by a specific, small group of people at a narrow point in time. It had momentum, for centuries. Still, most of the witnesses to this conflict are non-canonical texts that, for the most part, were wiped off the face of the earth. We’re very fortunate to have any evidence of them at all, fragmented as they are.

The Gospels themselves are mostly clear about Peter’s authority, but if we consider everything discussed above, an alternate, potentially earlier reading of the Gospel of John would contain a woman named Mary who:

- Was loved by Jesus

- Made the central Christological confession of faith

- Was the first witness of the resurrection

- Was given the first apostolic commission to spread the Gospel message that Jesus was risen

In my opinion, that is potentially a threat, not only to Peter’s authority, but to the exclusive authority of men to guide the fledgling church, and potentially to the patriarchal social order itself. It’s almost surprising that Mary Magdalene remains in any texts at all.

When the pieces come together in that way, this new scholarship around Mary Magdalene’s identity begins to feel positively explosive. I’d like to point out that that although these ideas challenge tradition, they require no unorthodox interpretation; you don’t have to squint and stand on your head to see this picture. You don’t have to rely on heterodox texts or invent mystical importance for Mary Magdalene, and you certainly don’t have to believe she was Jesus’s wife. Mary Magdalene is, in my opinion, capable of shaking the Church to its foundations based on her apostolic identity alone, and we have Elizabeth Schrader Polczer to thank for her scholarship that finally brings this into tight focus.

Looking ahead

I believe that the work Elizabeth Schrader Polczer is doing is critically important, not only for those of us devoted to Mary Magdalene, but also for New Testament studies more broadly, and Christianity as a whole. It has been a very long time since I’ve felt as inspired, as energized, and honestly, as hopeful, as I am now. I’m turning to the Gospels with new eyes these days, and with an uncharacteristically open heart. It’s refreshing. That said, I’ve also lost patience with tradition and the stingy refusal to credit women, particularly Mary Magdalene, for their contribution to the founding of Christianity.

He is risen; we know because Mary Magdalene said so.

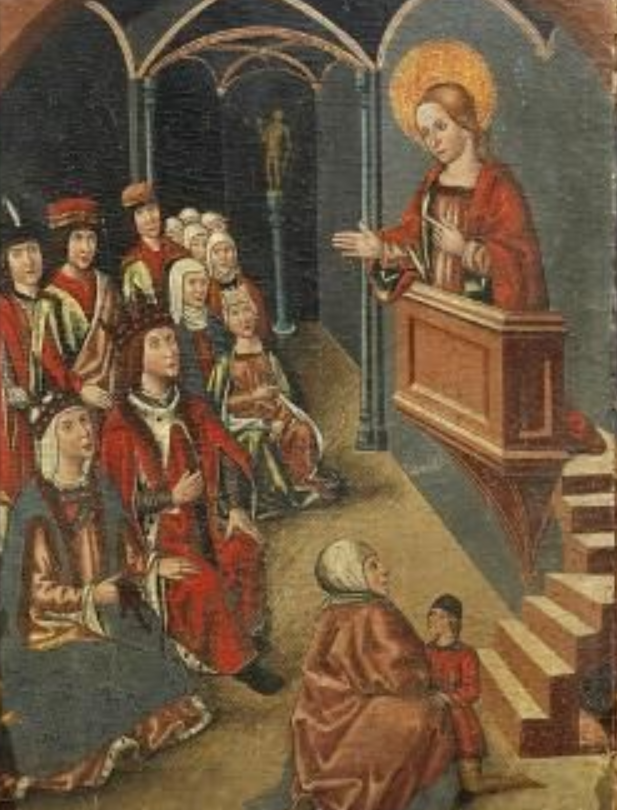

Mary Magdalene preaching before the princes, detail from the Altarpiece of Mary Magdalene, by an unknown Aragonese artist (late 15th century).